All SMEs located far from markets face uncertainty in sourcing inputs that can affect the volume and consistency of production as well as creating difficulties in selling what they produce. Female entrepreneurs’ access to markets can be further constrained by social norms against women travelling alone or without a male relative, thereby impeding access to critical information about markets. In addition, women-owned businesses tend to be smaller, with fewer employees, and lower average sales. As a result, the volume requirements in some markets may be a barrier to their participation, particularly in large, centralized, domestic and international markets.

Moreover, information about the type of goods in demand, quality standards, branding and presentation requirements, and pricing, is not as readily accessible to women entrepreneurs who are unable to regularly interact with buyers. Established buyers and sellers can engage in collusive activity that impedes new entrants from participating in a market. For example, some Latin American women fishers receive lower prices because they sell in smaller volumes to powerful intermediaries who then set the price (United States Agency for International Development 2005). In combination, these factors can prevent women from accessing new and larger markets. To help address these issues, under its Public Procurement Strategic Plan (2002–2004), the Chilean government created an e-Procurement platform, ChileCompra (“Chile Buys”), that enables private sector businesses to bid electronically to provide goods and services to the government (Chile, Ministry of Finance 2016). ChileCompra increases the transparency of public sector demand-side data and automates and streamlines the Chilean government´s sourcing process, resulting in easier, equal access for all SMEs. It also facilitates WSMEs´ ability to participate directly in the public sector procurement process without preexisting relationships with government officials and with the added convenience and efficiency of doing so through a digital platform. The result has been a more competitive bidding process for government contracts.

Another bright spot in relation to WSMEs´ access to markets has been global supply chains. Goods whose component parts were once produced and assembled in one location may now be manufactured in factories on different continents. In some industries, such as textiles and apparel, this has increased the demand for female workers (World Bank Group and World Trade Organization 2020). In addition, SMEs, including women-owned firms, are increasingly exposed to foreign markets through their integration into larger firms´ supply chains (World Bank Group and World Trade Organization 2020). However, women-owned businesses may lack the financial resources that allow their male counterparts to successfully weather supply chain realignments, such as when larger companies decide to shift aspects of their production closer to larger consumer markets or to automate labor-saving tasks within supply chains (World Bank Group and World Trade Organization 2020).

Using Technology to Access Markets

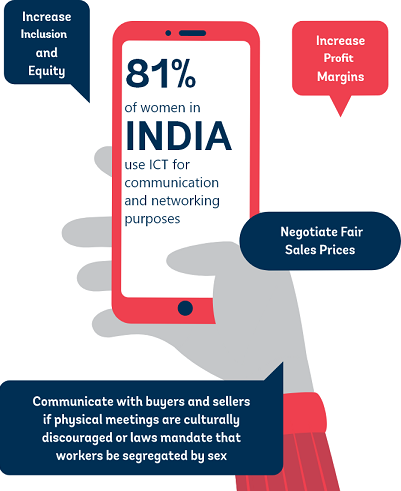

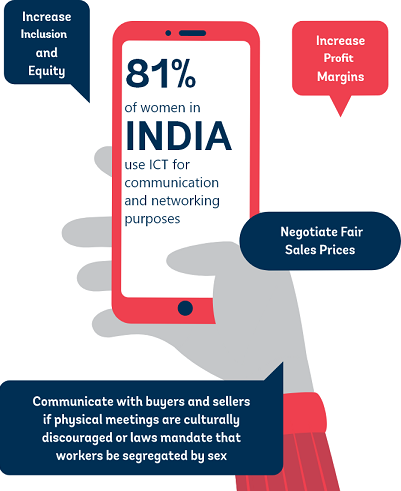

ICT permits more small-scale entrepreneurs to participate in markets and provides innovations in logistics chains that can lead to closer links between buyers and sellers. In rural areas, mobile phones provide entrepreneurs, including women, access to local markets and enable them to carry out financial transactions, including arrangements for sale and delivery of goods and services. Developing country governments, such as Nigeria, partner with mobile operators in e-Wallet initiatives to use electronic vouchers delivered by phone to coordinate distribution of inputs, including improved seeds and fertilizers, to remote areas (Suri and Jack 2016). Women entrepreneurs are able to use mobile phones to connect directly to a virtual market platform that is a transparent, open, and trustworthy space in which to gauge market demand, negotiate fair sales prices, and arrange delivery with agents and traders, potentially eliminating intermediaries and increasing profit margins. Conversations via phone and SMS are a convenient and efficient means for female entrepreneurs to communicate with buyers and sellers if physical meetings are culturally discouraged or laws mandate that workers be segregated by sex. Fully 81 percent of women in India use ICT for communication and networking purposes, including female business owners who use ICT to create and maintain marketing channels, collect customer information, and improve efficiencies in their business processes (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific 2013). Data analytics can also be used to help identify and reduce collusion between suppliers.

Novel technological advances have been made recently in the field of blockchain digital ledgers that eliminate the need for transaction validation by third-party entities and lower the costs related to working capital and cost of goods sold for SMEs. Blockchain is a decentralized, distributed, and secure ledger that records information about commercial transactions (World Bank Group 2020a (forthcoming)). Blockchains are protected by cryptographic technologies that render them virtually invulnerable to corruption or hacks (World Bank Group 2020a (forthcoming)). The net result of using blockchain is that suppliers have lower working capital costs and buyers have a lower cost of goods sold. All of the above-mentioned digital technology advances can be used to increase inclusion and equity among female and male entrepreneurs conducting business in the same sector.

Goods travel increasingly long distances to reach the end-user, which has created the need for efficiency gains in transport and logistics. Mobile and digital communication, such as text messages between entrepreneurs and product buyers, can confirm pick-ups and monitor the movement of goods, including real-time updates about the quantity and condition of products, as well as estimated arrival times. These technical advances in logistics help eliminate product waste in developing countries where, for example, food loss reduces income by at least 15 percent for 470 million smallholder farmers and downstream value-chain actors (Food and Agriculture Organization 2013). SMEs´ increased integration into the international movement of goods and global value chains (GVCs) has become more ubiquitous. Virtual marketplaces (VMPs) or “e-commerce” platforms are increasingly accessible to SMEs in developing countries through the expanded use of improved digital technologies and make significant contributions to this phenomenon. E-commerce ventures present many advantages for WSMEs: access to a larger, “virtual” customer base; freedom from geographic limitations; opportunities to engage in commercial activity around the clock; and lower business operating costs due to the elimination of the need for a brick-and-mortar storefront. In addition, VMPs have the potential to lower trade barriers for women business owners by bringing female producers and traders closer to markets and making it easier for female entrepreneurs to borrow (World Bank Group and World Trade Organization 2020).