Case Study

Successful Inclusion of Technology into Project Design and Implementation

Introduction

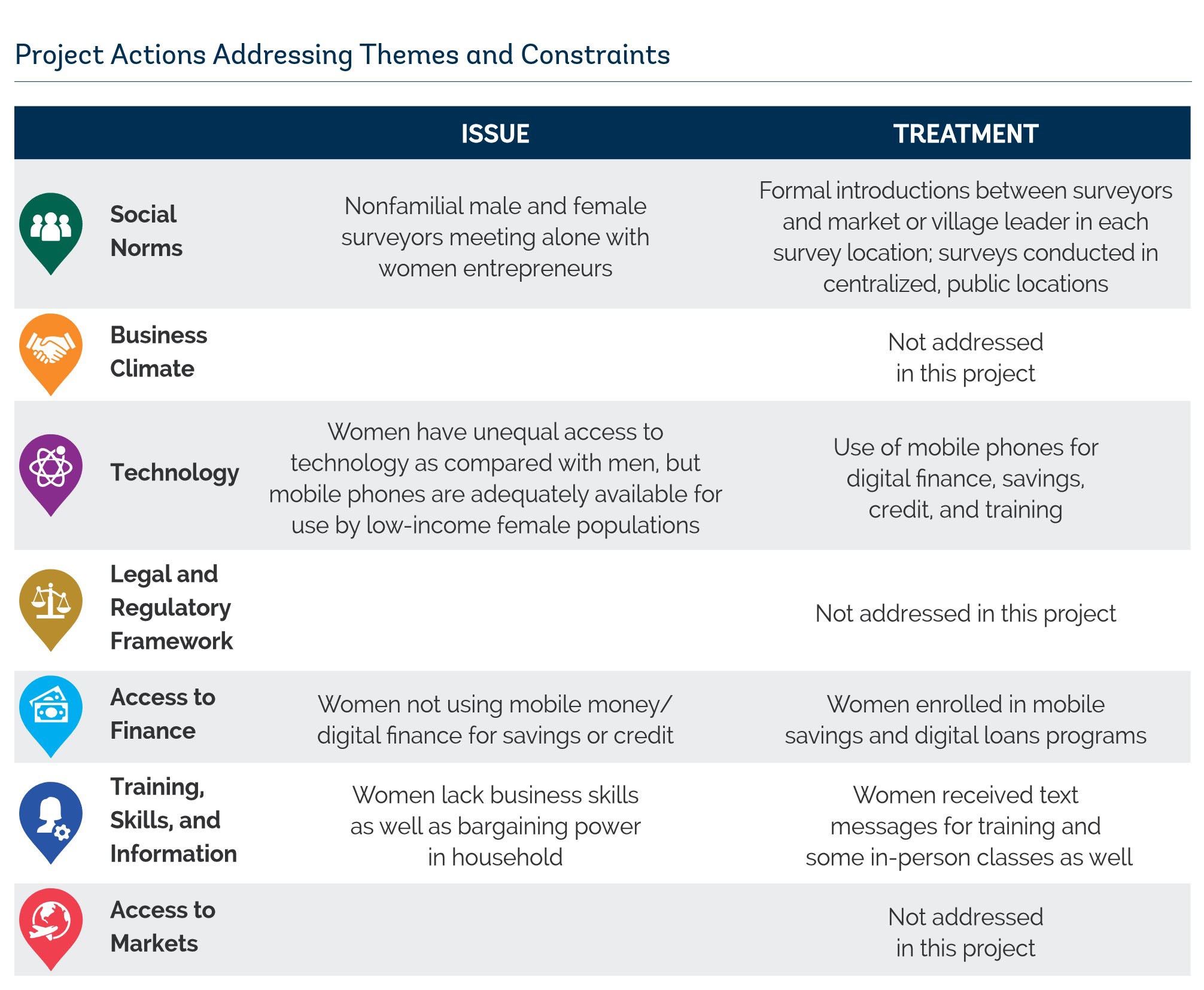

The Business Women Connect mobile savings case study highlights a project that focused on helping Tanzanian women microentrepreneurs increase mobile savings. It provides an example of the overarching themes and constraint areas highlighted in this toolkit, the actions undertaken to address the most significant issues, and the incorporation of a digital tool to facilitate project implementation.

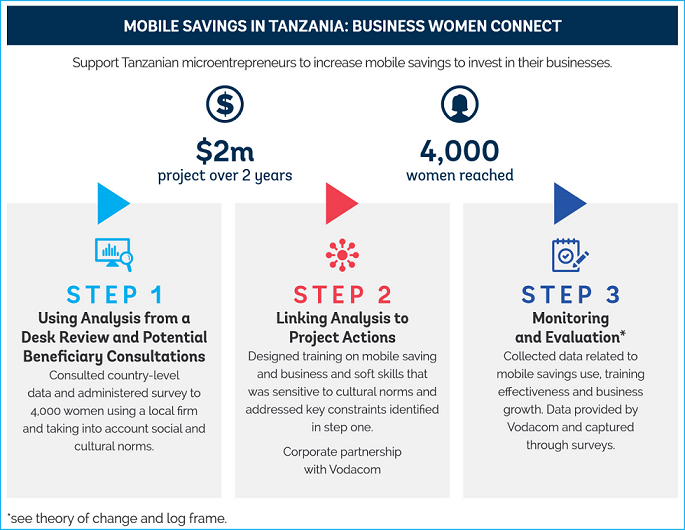

In 2016, the WBG Africa Gender Innovation Lab along with Center for Global Development (CGD), TechnoServe (NGO), Arifu, and the ExxonMobil Foundation launched the Business Women Connect pilot in Mbeya and Dodoma, two cities in northern Tanzania. The two-million-dollar project was implemented over a period of 27 months with 4,000 female microentrepreneurs, primarily market and street vendors, as beneficiaries. The project’s objective was to improve women microentrepreneurs' access and ability to effectively use mobile savings technologies as a means of expanding their businesses. This case study describes the project design process: the analysis conducted, the tools used to formulate gender-sensitive activities, and the mechanisms included to monitor progress.

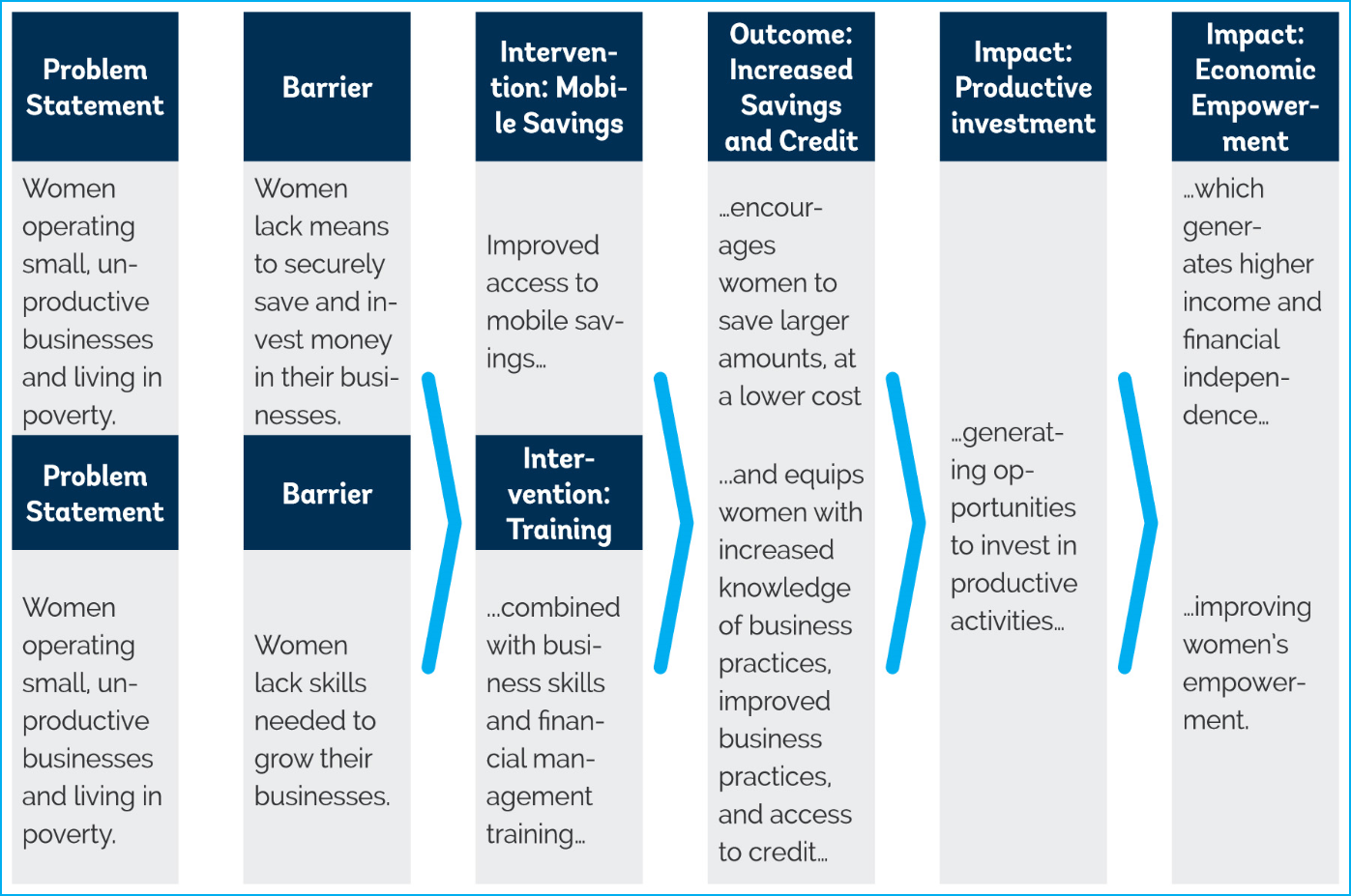

Evidence suggests that microentrepreneurs are more likely to use savings than credit to finance their businesses. Women, in particular, however, struggle to save money, as they are often expected to share their resources among family members. Mobile savings accounts can be especially useful for women business owners because they keep resources confidential and inaccessible to family members and thus remain more readily available for business use. The Tanzania project tested the use of mobile savings and business skills training, both separately and together, to ease constraints that impede women microentrepreneurs from financing the growth of their businesses.

Project Overview

Component 1: Mobile Savings

Women microentrepreneurs participated in a 2.5-hour training covering the general concept and primary benefits of mobile savings. They also participated in “learning-by-doing” exercises and viewed instructional videos showing how to create a mobile savings account and explaining the benefits of M-Pawa, a Vodacom savings platform linked to M-Pesa. The M-Pawa platform allows customers to save money through interest-bearing mobile savings accounts and to qualify for uncollateralized instant digital microloans.

Component 2: Business Skills Training

Over a period of three months, beneficiaries took part in weekly 2.5-hour, face-to-face training sessions that covered basic business skills and financial literacy. The curriculum aimed to teach and motivate female microentrepreneurs to set business goals, identify business opportunities, and negotiate with suppliers — all with the aim of putting ideas into practice and mobilizing finance for their businesses generated through their own savings.

Step 1: Using Analysis from a Desk Review and Potential Beneficiary Consultations

Desk Review

The project team consulted country-level data that revealed that female-owned businesses underperformed those owned by males and that women business owners are a predominantly unbanked population reliant on informal savings. Research indicates that facilitated access to funding when combined with business skills training is effective in helping women microentrepreneurs start and grow their businesses (Buvinic, Furst-Nichols, and Courey Pryor 2013). Mobile savings, in particular, shows promise as an effective means of improving women’s business financing.

To assess the potential of an intervention to promote the use of mobile savings in Tanzania, the team conducted a desktop analysis that reviewed data on digital financial services. At the time, only 34 percent of Tanzanian women had formal bank accounts, as compared to 45 percent of Tanzanian men (Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2014). In addition, less than a third (27 percent) of Tanzanian women held mobile money accounts, versus 38 percent of their male counterparts Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2014).

Consultations

Process. To understand why women were struggling to access finance and to determine the need for business training, the project team developed an initial screening for microentrepreneurs and designed a survey instrument. About 4,000 women were selected to participate in the survey based on the following eligibility criteria: (1) owns her own business; (2) owns a mobile phone; (3) owns a functional Vodacom SIM card; (4) can pass a basic literacy test; and (5) is interested and available to participate in a 12-week business training program.

The survey was administered by Savannas Forever, a Tanzania-based survey firm, and elicited information about sociodemographic characteristics of the women microentrepreneurs, their business earnings and practices, any business and household-related shocks they had experienced, their coping strategies, their familiarity with or use of mobile money and savings accounts, and their intra-household decision-making processes.

The project team took steps to address cultural and social norms that might impede survey administration or discourage participation. For example, the team paid particular attention to making formal introductions of the program to the market or village leader in each survey location. In addition, the surveys were administered to the women microentrepreneurs in a central, public location, such as a government building, school, or established restaurant. After completing the questionnaire, the women were each given a nominal amount to assist with transportation expenses to and from the survey location. Trained enumerators completed all data collection using a digital enabler, Google Nexus tablets, which had the questionnaire preloaded. At the end of every day, each enumerator uploaded the collected data to a cloud-based server and returned the tablet to their team leader. The uploaded data were checked daily to verify their accuracy.

Results. The survey findings highlighted several key challenges faced by the women, including (1) limited financial literacy or knowledge of business and related soft skills; (2) lack of incentives and opportunities to acquire skills due to social norms; (3) limited access to finance that met their needs; and (4) lack of tools, inputs, and collateral. The survey also pointed to design elements that would improve the project’s chances of success, such as hiring a team of all-female trainers and inviting the women’s husbands to join the training.

The information that emerged from the survey enabled the project team to identify significant advantages that mobile savings would extend to women in the pilot, including improved safety, privacy, and confidentiality in managing savings so that it could be invested to expand their businesses. Information from the survey also indicated a positive correlation between savings and increased profits that strengthened when women entrepreneurs applied improved business skills. The project team noted that if women microentrepreneurs were not equipped with business knowledge on how to grow their firms, even if savings were available, they might not use the funds efficiently and effectively to invest successfully in business expansion. Although the project team could find past interventions that independently measured the effectiveness of mobile banking products and business skills training for women entrepreneurs, the desktop research found little evidence of a combined effect. The intervention aimed to close this knowledge gap.

Step 2: Linking Analysis to Project Actions

Putting It All Together

To address knowledge gaps revealed by the analysis, the team developed bite-sized modules of mobile savings instruction covering (1) the general concept of savings and its benefits; (2) an introduction to M-Pawa; (3) registration for M-Pawa and how to use it; and (4) enrollment in a text-message-based learning platform, Arifu. Arifu encouraged the women to set personal savings goals with the option to receive weekly SMS savings reminders and motivational “push” messages related to savings.

To enhance women’s business and soft skills, the project implemented a 2.5-hour, 12-module, course administered over the span of 12 weeks, covering the following topics: business expansion and profitability; personal and professional efficiency; finance and record-keeping; and entrepreneurship and business planning. Each topic was reinforced through an innovative, interactive mobile learning platform designed for the project. The course-work also emphasized the importance of developing personal effectiveness and perseverance and the benefits of a more gender-equal society.

The analytical findings and survey information collected in Step 1 were incorporated into the project design. For instance, to diminish possible resistance to the program from the husbands of the women microentrepreneurs, team members invited them to attend the trainings. To address cultural issues related to women interacting in public with men who were unrelated to them, the project team recruited an all-female cadre of skilled instructors to conduct the training sessions. Taking into consideration other household and business responsibilities competing for the women’s time, the project team scheduled the training to take place at times and locations best suited to their multiple obligations.

Corporate Partnership with Vodacom

The project team determined that, among the product options, Vodacom's M-Pawa mobile finance product was uniquely positioned to support the project because it permitted customers to deposit money into separate interest-bearing savings accounts. M-Pawa did not have a strong following among women microentrepreneurs, however, who were unaware or unconvinced of its financial and practical benefits. This represented a market opportunity for Vodacom. When the project team approached Vodacom with the pilot concept and the opportunity it offered to increase the number of women customers of M-Pawa, Vodacom was enthusiastic about the prospect. As part of the corporate partnership, Vodacom agreed to provide the project team with data on each female participant's M-Pawa account, including daily transactions and microloan disbursements and repayments, provided the women signed consent forms and the data was kept anonymous. This data enabled the project team to track mobile savings deposits, including their size and frequency.

The Business Women Connect pilot incorporated a rigorous evaluation, including the previously mentioned baseline survey administered between May and July of 2016, a midline survey conducted about 12 months after the baseline, and an endline survey conducted 18 months after the baseline. To track project progress, the team also selected indicators at the design stage that could be easily monitored and reported, enabling them to gauge the effectiveness of the gender-related project components.

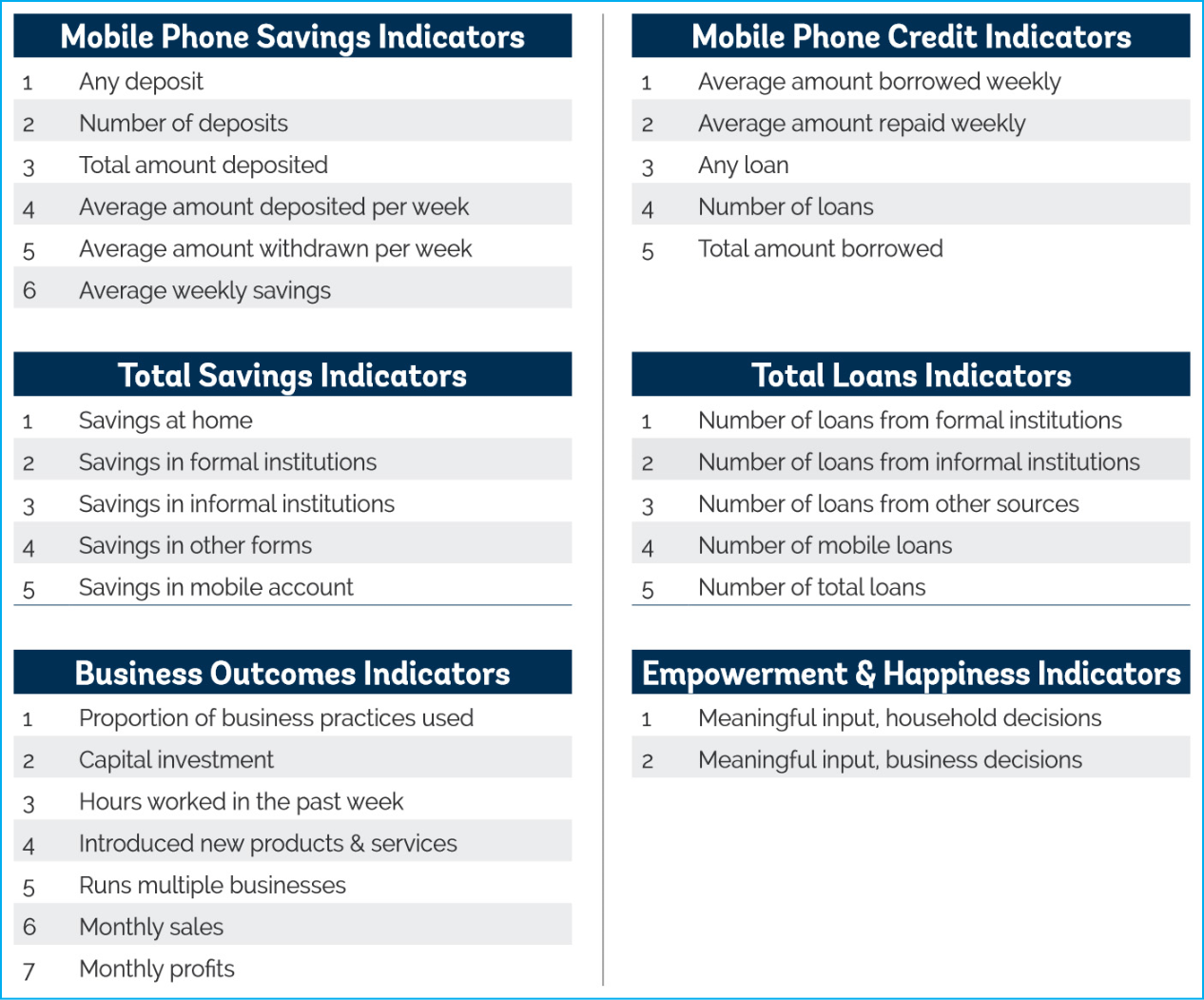

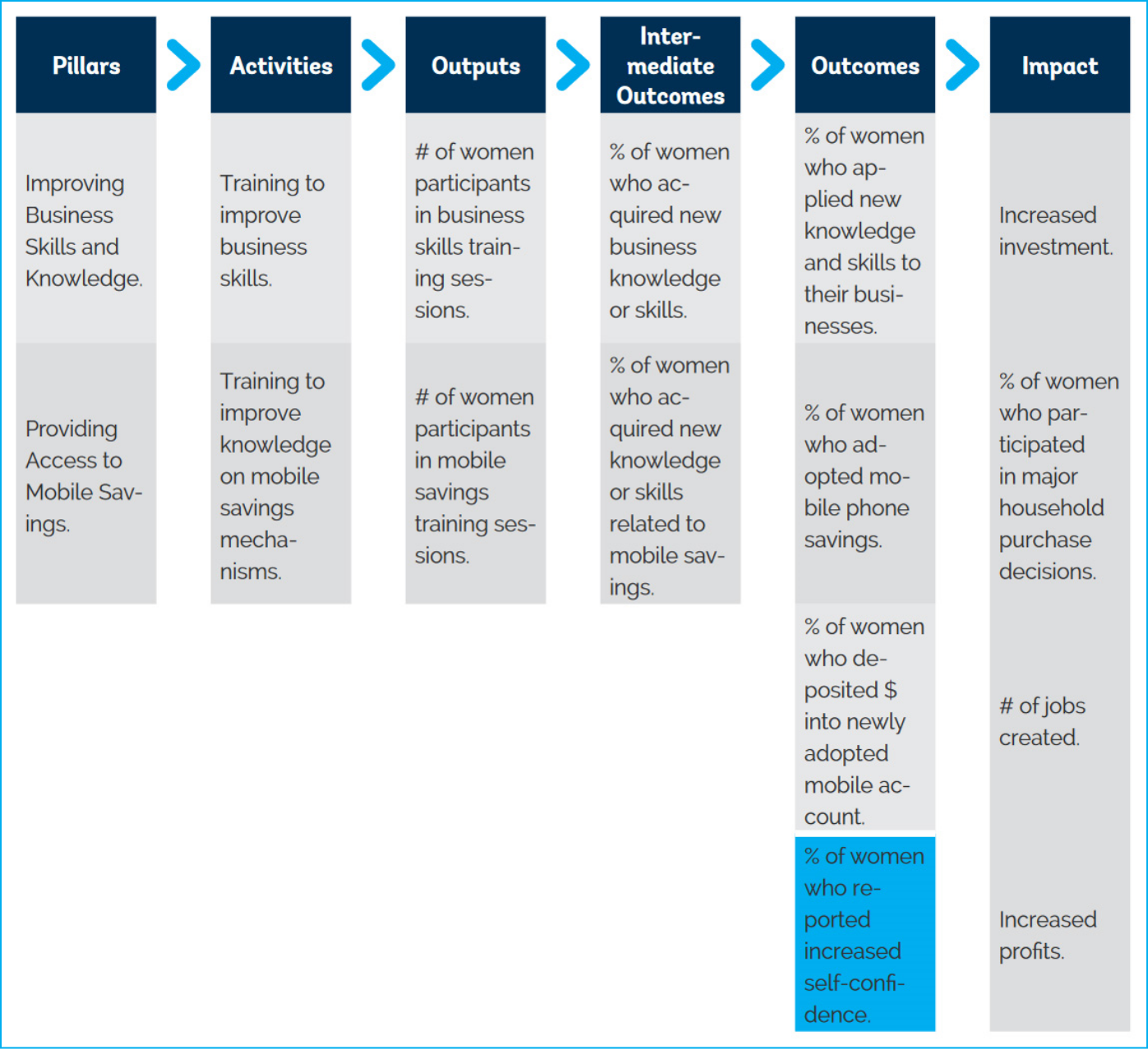

Indicators for Business Women Connect, Tanzania

Theory of Change

Log frame

Results

Beneficiaries participating in the mobile savings intervention alone saved twice as much money weekly through M-Pawa than did the control group. The mobile savings intervention also increased new business creation and the level of resilience among existing businesses encountering unexpected financial shocks.

In addition, borrowing from M-Pawa increased, and women microentrepreneurs who established mobile money savings accounts were 14 percent more likely to receive a mobile loan. The women who participated in both the mobile savings and the business skills training saved almost four times as much money on a weekly basis than did those not participating in either activity. It is important to note that when the female microentrepreneurs began saving through M-Pawa, data indicated that they were not necessarily saving more overall, but rather shifting the savings cache at home to secure mobile accounts.

Adding the business training on top of the mobile savings intervention led to substantial increases in business investment: business practices such as recordkeeping and financial planning improved, capital investment went up by about 40 percent, total hours worked by the women increased by more than three per week, and the likelihood of individual women running multiple businesses or introducing new products also went up. The research team is currently conducting a longer-term follow-up mobile phone survey to examine how this increased business investment translated into greater profitability.

The increased savings also improved women’s intrahousehold decision-making power. Women who were encouraged to open mobile savings accounts indicated that they had greater decision-making power over their business and household expenditure allocations as compared to women who did not open mobile savings accounts.